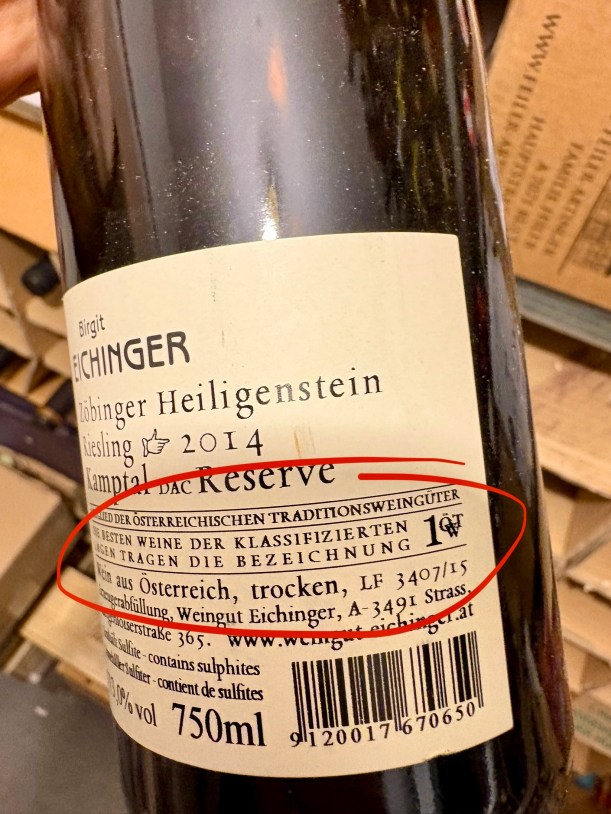

Have you ever wondered what the term ‘Erste Lage’ or 1 ÖTW on a bottle of wine from Austria means? I attended a seminar at the bi-annual Trade Austrian Wine tasting last week that explained the story behind the ÖTW and forthcoming changes coming into place.

First a quick overview of the current legal framework that applies to Austrian wine. Like other European wine producing countries a tiered classification system exists with specific labelling:

- ‘Österreichischer Wein’ means that the wine is made from grapes grown anywhere in the country. The wine can be from a single grape variety but not certain protected varieties such as Blaufränkisch. There are also some not very challenging minimum and maximum limits on must weight and yield.

- ‘Landwein’ means the wine is made from grapes from an area with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). There are three: Weinland, Steirerland and Bergland. Each area has an approved list of grape varieties but the list is long and the areas are large.

- ‘Qualitätswein’ is indicated by the red top with a white stripe through it. These wines are from grapes coming from an area with protected status (PDO). The wines are tasted and tested to ensure they display typical characteristics of the region and meet more stringent minimum standards including must weight and maximum yields.

‘Qualitätswein’ can be labelled ‘Kabinett’ if it is not enhanced within the winery in any way and is less than 13% ABV. If labelled ‘Reserve’ the wine will be 13% ABV or over.

‘Qualitätswein’ may also be labelled Districtus Austriae Controllatus (DAC). This means that it comes from one of 18 regionally typical controlled areas for example Weinviertel, Wachau or Leithaberg. Each DAC has quite a limited list of permitted grape varieties and the wines are tasted by a panel to approve typicity. Anything falling outside the scope or from a non-permitted variety can only be labelled Landwein.

Now within the DAC geographical area there are further spatial refinements: Gebietswein means it just corresponds the DAC area, Ortswein is from a particular village area and Riedenwein is from a single vineyard.

This is where the ÖTW comes in.

Founded in 1991 the ÖTW (oo – tay – vay) is a trade Association. It was set up to create a vineyard classification system designed to help consumers get an even better understanding of what to expect from the wine inside the bottle. Anything that can help in this respect is of course a good thing.

Started by a group of wineries in Kamptal and Kremstal the ÖTW splits the Riedenwein category down into three ascending subcategories: Ried Lage , Erste Lage and Grosse Lage. So far vineyards have only been classified as Erste Lage / 1 ÖTW but in time the intention is to elevate some of these to Grosse Lage.

The model is evidently similar to the classification of vineyards in Burgundy where distinct from village and lieu dit wines there are classified premier and grand cru vineyards. However as with the Bordeaux classification Chateaux in 1855 the vineyards in Burgundy were categorised back in the 19th Century according to the market value achieved of the wines, as a measure of quality and status.

So interestingly the ÖTW claims that vineyards in their system are not classified on the subjective bases of quality and price. Instead the ‘significance’ of the plot is measured using multiple parameters. These include: historical and cultural, physical characteristics, the number of wineries producing from the vineyard also average price and variance over time. The wines produced are also evaluated via blind tastings by growers and international experts and the consistency of their performance over time.

Anecdotally we tasted three wines from Ried Heiligenstein 1 ÖTW which were all Riesling but from three different producers: Birgit Eichinger 2022, Allram 2019 and Bründlmayer 2015. The wines were all of the highest quality with thrilling concentration and persistence. They were layered and complex and showed how age worthy they can be.

This was obviously too small a sample to be able to divine clear vineyard characteristics but the tasting certainly backed up my experience that 1 ÖTW on the label means that the winery has set out with serious intent to make a high quality wine that speaks of its origin.

The ÖTW system has expanded and is now used by members in Kamptal, Kremstal, Traisental, Wagram, Vienna, Carnuntum, Thermenregion and the Weinviertel.

A notable exception to this list is the Wachau and its not clear why the producers there don’t feel the need to participate. Speculating, the region is perhaps more domestically and internationally well-known and they have their own quality hierarchy: Stienfeder, Federspiel and Smaragd so demand and recognition is probably already strong enough. Also many single vineyard wines are produced and I wonder if the number of monopole vineyards are sufficient to make vineyard classification less important than producer name? Research for another day.

The ÖTW is however on the up and has in principle be approved for adoption by the ministry of agriculture into law. As with any change in wine law there are those that are not convinced and currently an appealed against adoption is being determined in the courts. Watch this space.